A dream is a multifaceted phenomenon. It can refer to experiences that unfold during deep sleep, or it can encompass the aspirations and desires that persistently occupy our thoughts while we are consciously awake.

When it comes to dream reports obtained by awakening a sleeping individual, their accuracy in conveying subjective experiences during sleep can vary. At one end of the spectrum, the level of consciousness during sleep can fluctuate, affecting our ability to remember dreams. This recollection can range from vivid to fleeting, depending on the specific brain state at the moment of awakening. Interestingly, many people claim they rarely dream, but research from controlled awakenings in sleep laboratories reveals that we often underestimate both the frequency and depth of our consciousness during sleep. Conversely, individuals who report a lack of dreaming due to neurological conditions do not show a higher likelihood of memory disorders, indicating that the absence of dream reports likely signifies a lack of dream experiences rather than a fundamental alteration in memory function alone. Further research may shed more light on this topic, as studies suggest heightened activity in memory-related regions within the medial temporal lobe during REM sleep.

On the other end of the spectrum, some might argue that we remain entirely unconscious throughout sleep and that dream reports are mere confabulations during the transition into wakefulness. Although this perspective is difficult to conclusively refute (similar to the challenge of proving one is not a zombie when awake), it seems highly improbable. When we’ve just experienced a vivid dream, it is hard to believe that it was spontaneously concocted upon awakening. Supporting this view, dream reports often align well with the time elapsed in REM sleep before awakening. Additionally, in cases of REM sleep behavior disorder, where muscle atonia is disrupted, the physical movements of the sleeper often correspond to the content of their reported dream.

Reports obtained upon awakening from deep NREM sleep can be more challenging to evaluate due to the disorientation associated with increased sleep inertia. Nevertheless, there is evidence suggesting that dream consciousness can indeed occur in NREM sleep and is not solely a recollection of earlier REM sleep dreams. For instance, it is sometimes possible to influence dream content by introducing sounds during NREM sleep, and “tagging” NREM reports. Certain NREM parasomnias, such as sleep talking and sleep terrors, correspond to reported dream experiences. “Full-fledged” dreams have even been reported upon awakening from the initial NREM sleep episode before any REM sleep has occurred, and in cases where a nap consists solely of NREM sleep.

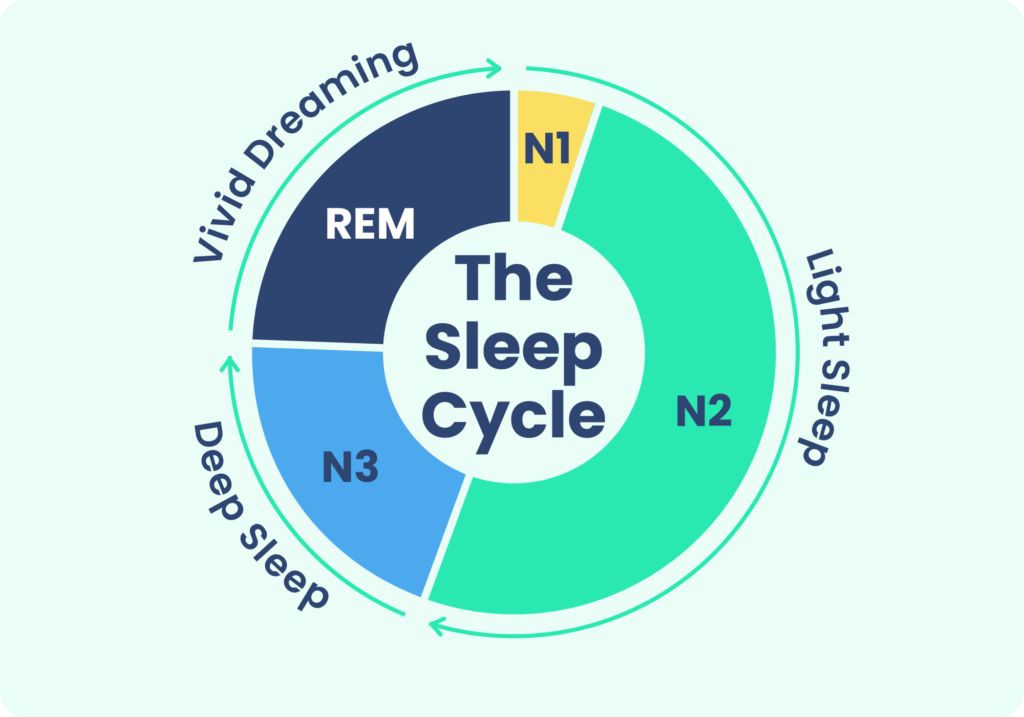

Cycle of Sleep

A sleep episode commences with a brief stint in NREM stage 1, progressing through stage 2, followed by stages 3 and 4, culminating in the arrival of the REM stage. Interestingly, individuals don’t dwell in REM sleep for the entire night; instead, they cycle through stages of NREM and REM throughout the night. NREM sleep constitutes a substantial portion, roughly 75 to 80 percent, of the total time spent asleep, leaving REM sleep with the remaining 20 to 25 percent. The initial NREM-REM sleep cycle typically lasts between 70 to 100 minutes. Subsequent cycles, however, tend to be more extended, lasting approximately 90 to 120 minutes.

In the case of normal adults, REM sleep becomes more prominent as the night unfolds, often reaching its zenith during the final one-third of the sleep episode. As the sleep episode progresses, stage 2 dominates the NREM sleep stages, and stages 3 and 4 may even become less prevalent or fade away altogether.

Physiological Changes During NREM and REM Sleep

| Physiological Process | NREM | REM |

| Brain activity | Decreases from wakefulness | Increases in motor and sensory areas, while other areas are similar to NREM |

| Heart rate | Slows from wakefulness | Increases and varies compared to NREM |

| Blood pressure | Decreases from wakefulness | Increases (up to 30 percent) and varies from NREM |

| Sympathetic nerve activity | Decreases from wakefulness | Increases significantly from wakefulness |

| Muscle Tone | Similar to wakefulness | Absent |

| Blood flow to the brain | Blood flow to the brain | Increases from NREM, depending on brain region |

| Respiration | Decreases from wakefulness | Increases and varies from NREM, but may show brief stoppages; coughing suppressed |

| Airway resistance | Increases from wakefulness | Increases and varies from wakefulness |

| Blood flow to the brain | Is regulated at a lower set point than wakefulness; shivering initiated at a lower temperature than during wakefulness | Is regulated at lower set point than wakefulness; shivering initiated at a lower temperature than during wakefulness |

| Sexual arousal | Occurs infrequently | Greater than NREM |

The Interpretation of Dreams

Sigmund Freud’s groundbreaking work, “The Interpretation of Dreams,” published in 1900, eloquently delves into the intricate relationship between conscious and unconscious thought processes. However, it remains a subject of debate whether dreams hold the profound significance ascribed to them by Freud and his contemporaries, and psychoanalytic interpretations of dreams have somewhat fallen out of favor. Nevertheless, it’s likely that most individuals, in their private contemplations, ascribe some importance to the content of their dreams.

In more recent studies on dreams, intriguing patterns emerge: about 65% are associated with emotions such as sadness, apprehension, or anger; 20% with happiness or excitement. What’s somewhat surprising is that only 1% are linked to sexual feelings or acts.

Adding to the ambiguity surrounding the purpose of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep and dreaming is the fact that depriving humans of REM sleep for up to two weeks seems to have little or no apparent impact on their behavior. These studies involved waking volunteers whenever their EEG recordings indicated REM sleep. Although these subjects tend to compensate by experiencing more REM sleep after the deprivation period, they display no evident adverse effects. Similarly, individuals taking certain antidepressants like MAO inhibitors, which often reduce REM sleep, do not exhibit obvious ill effects, even after extended treatment periods spanning months or years. This benign nature of REM sleep deprivation contrasts starkly with the severe consequences of total sleep deprivation (as discussed earlier). These findings suggest that we can manage without REM sleep, but non-REM sleep is vital for our survival.